It may not be for everyone, but a new study suggests that the smooth stride of a gentle horse may help stroke survivors regain lost mobility and balance years after their brain attack.

“I don’t think we’re ready to say that once you’ve reached the last phase of stroke recovery, you should get on a horse,” said Dr. Daniel Lackland, a spokesperson for the American Stroke Association.

But, it’s “exciting” that many of these patients saw improvements with therapies “outside of what’s available in traditional stroke rehabilitation,” he added.

None of the stroke survivors in the study had severe disabilities, but they did have lingering problems with essential functions like balance, walking and memory.

Researchers found that two unconventional therapies — horseback riding and music-and-rhythm therapy — seemed to help many of these patients.

Lackland also pointed to the bigger picture: The study showed that improvements can be made long after a stroke occurs.

That, in itself, has not been clear, according to Lackland. Most research, he said, has focused on shorter-term stroke recovery.

Senior study researcher Dr. Michael Nilsson agreed.

“A very important message is that it’s never too late to improve functions, to learn or relearn, because of the capacity of our brains,” said Nilsson, a rehabilitation medicine specialist and professor at the University of Newcastle in Australia.

Stroke rehabilitation begins as soon as a patient is stable. The specifics depend on the damage the stroke has caused: Some people need physical therapy to try to regain the function of their limbs; some need speech and language therapy; others need help with getting back to work.

But, Lackland said, it’s not known whether those same conventional approaches continue to help in the later phases of recovery.

In fact, he said, stroke survivors usually do not continue rehab for the long haul.

According to Nilsson, “the general opinion has been — and in many cases still is, unfortunately — that in late phase after stroke, there is nothing further to be achieved.”

But, he said, researchers are increasingly looking at late-phase recovery, as they learn more about the brain’s “plasticity” — its ability to adapt and recover from injury.

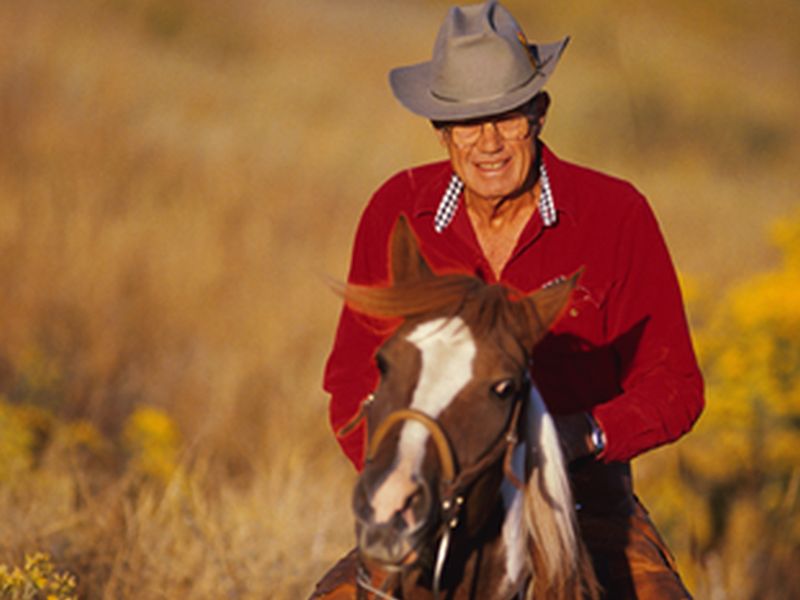

The idea behind horseback riding is, partly, that the movement of the horse gives a “sensorimotor experience” that is similar to normal human walking, according to Nilsson’s team.

On top of that, it engages people mentally and socially.

Similarly, the researchers say, the music-and-rhythm therapy stimulates the body, senses and mind: It requires people to listen to music, and move their hands and feet in tricky patterns based on cues they hear and see.

For the study, Nilsson’s team randomly assigned 123 stroke survivors in Sweden to either one of those therapies or to a comparison group that stuck with standard care.

Patients in both treatment groups met with therapists twice a week for 12 weeks.

Six months later, patients who went through either the riding or music therapy were showing better balance and mobility, versus those in the comparison group.

They also felt better: After six months, 56 percent in the horseback riding group believed their stroke recovery had progressed, as did 43 percent in the music group. That compared with only 22 percent of patients in the standard care group.

Lackland stressed that the study was small, so it’s hard to draw firm conclusions.

But he said the findings suggest that researchers should keep looking into nontraditional approaches to helping stroke survivors in the long term.

Is horseback riding or music therapy practical in the “real world?”

According to Nilsson, music therapy would certainly be more feasible. It requires therapists who know how to do it, he said, but their training would not be extensive.

Plus, Nilsson said, it could be done in rehab clinics, group settings or even in people’s homes.

Horseback riding, of course, requires a specific setting.

But Lackland said it would be interesting to figure out whether certain aspects of the therapy — like the socializing with other people or interaction with animals — had specific benefits.

For now, Lackland said that even simpler things, like taking a walk every day or trying to stay socially engaged, may be helpful for long-term stroke recovery. In the shorter term, he noted, physical exercise can help stroke patients recover not only physically, but mentally as well.

The findings are published in the July issue of Stroke.

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has more on stroke rehabilitation.

Source: HealthDay

Leave a Reply