Doctors plucked a wriggling roundworm from the brain of an Australian woman in the world’s first-known case of human infection with a parasite common in some pythons.

The woman, who had been experiencing worsening symptoms for at least a year, is believed to have gotten the infection from foraging and eating grasses where a snake had defecated.

“This is the first-ever human case of Ophidascaris to be described in the world,” Dr. Sanjaya Senanayake, a leading expert on infectious disease at Australia National University and Canberra Hospital, said in a university news release. “To our knowledge, this is also the first case to involve the brain of any mammalian species, human or otherwise.”

It is suspected that larvae of the Ophidascaris robertsi roundworm were also present in the 64-year-old woman’s lungs and liver.

Her symptoms began in January 2021 with abdominal pain and diarrhea, followed by fever, cough and shortness of breath.

“In retrospect, these symptoms were likely due to migration of roundworm larvae from the bowel and into other organs, such as the liver and the lungs. Respiratory samples and a lung biopsy were performed; however, no parasites were identified in these specimens,” said Karina Kennedy, Canberra Hospital’s director of clinical microbiology.

“At that time, trying to identify the microscopic larvae, which had never previously been identified as causing human infection, was a bit like trying to find a needle in a haystack,” she said in the release.

As the woman’s symptoms progressed, along with subtle changes in memory and thought processing, she underwent a MRI brain scan. It spotted an unusual lesion on the frontal lobe of her brain.

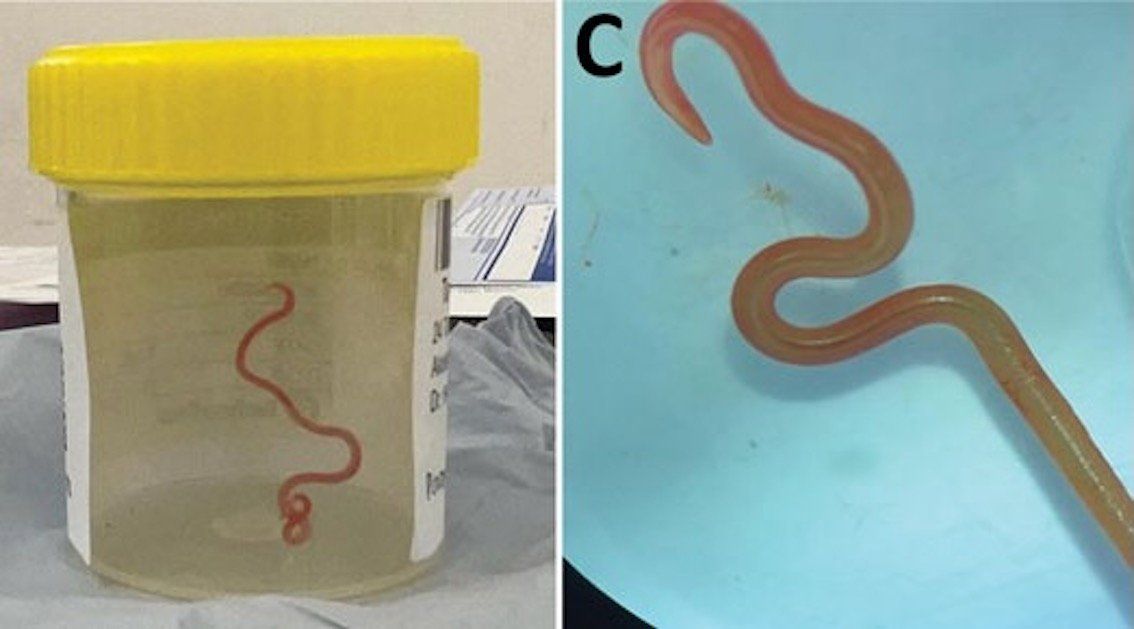

During brain surgery, doctors found the 3.15-inch roundworm. After doctors plucked it, still alive and wriggling, parasite experts identified it by appearance. Molecular studies confirmed their identification.

Doctors said the woman likely acquired the infection through foraging and eating spinach-like Warrigal greens along a lake where a carpet python had shed the parasite through its feces.

Normally, larvae from the roundworm are found in small mammals and marsupials, which are eaten by carpet pythons, snakes whose markings resemble Asian carpet patterns. That allows the life cycle to complete itself in the snake.

“There have been about 30 new infections in the world in the last 30 years,” Senanayake said. “Of the emerging infections globally, about 75% are zoonotic, meaning there has been transmission from the animal world to the human world. This includes coronaviruses.”

The Ophidascaris infection is not transmitted from person to person, however, so it won’t cause a pandemic like COVID-19 or Ebola, Senanayake said.

But, he added, both the carpet python and the parasite are found in other parts of the world, so future cases are likely.

The worm’s suspected larvae were present in some of the woman’s other organs, including her lungs and liver.

Ophidascaris robertsi is common among carpet pythons, Senanayake said. The parasite typically lives in the snake’s esophagus and stomach, and its eggs are shed in the python’s feces.

“Roundworms are incredibly resilient and able to thrive in a wide range of environments,” Senanayake said. “In humans, they can cause stomach pain, vomiting, diarrhea, appetite and weight loss, fever and tiredness.”

Safety is especially important when foraging where wildlife live, experts emphasized.

“People who garden or forage for food should wash their hands after gardening and touching foraged products,” Kennedy said. “Any food used for salads or cooking should also be thoroughly washed, and kitchen surfaces and cutting boards, wiped downed and cleaned after use.”

Infectious disease and brain specialists are continuing to monitor the patient.

“It is never easy or desirable to be the first patient in the world for anything,” Senanayake said. “I can’t state enough our admiration for this woman who has shown patience and courage through this process.”

The researchers’ findings were published in the September issue of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has more on parasites.

SOURCE: Australian National University, news release, Aug. 28, 2023

Source: HealthDay

Leave a Reply